This article has been cross-posted to ChroniclerSaga.com.

A couple of weeks ago, the hashtag #EditorAppreciationDay started on Twitter. It primarily centered around comic book editors at first, either having been a direct response to this article on Medium.com (which was originally titled “Why Image Comics Needs To Stop Demonizing Editors Now”) or simply having fortuitous timing. From my standpoint, the article is rather absurd; a blatantly knee-jerk reaction from an editor who was obviously wound up and poised to spew that response at his earliest opportunity.

But the article – primarily in its knee-jerk nature – serves to illustrate a related, but slightly different, point: Enough arrogant, uneducated douchewaffles shit on editors that many of them have built up the same sort of auto-spew defense system which sent Mr. Kwanza on his tirade (I call it a tirade more due to the lack of inciting incident than the body of the espoused sentiment).

I encountered this issue most poignantly when I posted a comment on Chuck Wendig’s blog over at Terribleminds.com a few months ago. The discussion was about self-publishing, and the comments turned toward the subject of editing. Chuck made a comment about being able to find inexpensive editing services, or possibly finding editors who will trade their services. When I asked if he knew where I might find editors within my price range, another commenter butted in with the following:

“By editing, are we talking book doctors, or proofreaders? Frankly, if you need someone else to tell your story, you aren’t much of an author in my opinion. Nobody went back over Pcaso’s work and fixed his brush strokes. Indies may not be masters, but they should be able tomprovide abuyabke product on their own or they’re not very independant in my mind.”

[All errors in the above text are in the original post. Oh, the irony.]

Guys like this, unfortunately, are the people who put editors like Kwanza on the hyper-defensive. The arrogance of a stance like this is staggering, and is shared by far too many independent authors. The “gatekeeper” narrative has been threaded through so much of the self-publishing community that many authors have wrong-headedly learned to take the idea of editing as an affront to their creative freedom. As a lifelong artist – in some vein or another – I’m baffled by this attitude.

Any artist worth their salt will tell you everyone suffers from “art-blindness”. You work on a piece for so long – could be a sculpture or a painting or a manuscript – you become blind to many of its faults. For every one you catch, two will slip past, because you’ve been staring at the thing so damned much everything just seems normal, even if it’s not.

Before I sent my manuscript to beta readers, a friend of mine did a pretty extensive proofread, and tore it apart. When I sent the 3rd draft to beta readers, they tore it up, too; they found all kinds of issues. When I finished the post-beta-read revision – the 4th draft – I sent it off to my story editor, and she tore it up. The story edit resulted in my 5th draft, and I did a 6th draft before sending it off to the copyeditor, because I’m anal. The copyeditor tore it up.

Seven extra pairs of eyes on my manuscript, and every single one of them found faults. And not faults I would consider some sort of subversion of my creative vision (whatever the fuck that means), but faults causing me to say to myself “Holy shit, I can’t believe I missed that.” My story editor, Annetta Ribken, not only helped me unify the language in my dialogue and shave away excessive prose (I’m a wordy bitch), but she found weak spots in my plot which, had they been left in place, did a disservice to the rest of the story.

See, writing a book is hard. It requires constant, relentless critical thinking, and sometimes you’re not on your A-game. There were points in my plot even I felt were weak, but after cranking out 130,000 words and revising them three times, I looked at those passages as “good enough”. Until Annetta got ahold of it. When someone else looks at a piece of art you’ve decided is “good enough” and, in a professional capacity, tells you “It’s not good enough.”, you damned well best take note.

It’s not to say Annetta and I didn’t disagree sometimes. There were points of contention I argued for. There were changes she suggested I didn’t make. But in every single case, when she told me something needed changing, I had to argue with myself long before I started arguing with her. I had to take a critical look at every single edit and say “Is this up to my standards?” In most cases, I had to agree it was not, and had to look within myself to find a way to elevate it.

The same was true of my copyeditor, Jennifer Wingard. I learned more about the mechanics of prose from her copyediting passes than through anything else I’d done over the two years I spent writing the manuscript. I learned what my crutch words were (“that” and “was” need to be burned with fire), I learned the repetitive mistakes I make in sentence construction, and I learned no matter how many times I read over the same manuscript, I’m never going to find every extra space or misplaced quote or incorrect punctuation. I learned that “blonde” has a very specific meaning, different from “blond” (while seemingly basic, I had no idea).

And yet, through both of these collaborations, I never once felt like I wasn’t in control of my manuscript. At no point did the editing process feel as though either of my editors were trying to steer my story or fuck with my voice. You know why? Because that’s the whole point of being an editor. They’re there to make your work better – to make it more you. A good editor looks at your prose and works with you to find ways to solidify it without tinkering with what makes it yours.

And I learned so much. Probably the most amazing thing about working with these two wonderful women: I markedly improved my knowledge and execution of my craft because of these collaborations. There is no better way to become a better writer than to have a professional constructively deconstruct your prose. Which is why it’s such a damned shame there are so many authors out there with such an adversarial view of editing and, by extension, so many editors who’ve built this ablative armor against even the smallest hint of a slight against their profession.

Editing is not subversive or adversarial. If it is, you either a) found a really god-awful editor, or b) desperately need to get your ego in check. In most cases, it’s probably the latter.

If you’re in need of a substantive story edit, check out Annetta Ribken over at www.wordwebbing.com. Her edits are geared toward continuity and plot, and are well worth your time.

For a hardcore mechanical copyedit, get in touch with Jennifer Wingard at www.theindependentpen.com. You’re probably doing everything wrong, and she’ll show you how to do it right.

I highly recommend the services of both. They had a phenomenal impact on CONSTRUCT, and I couldn’t be happier with the result.

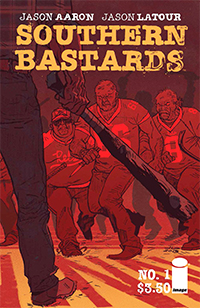

I just received my copy of the

I just received my copy of the  All of these factors lead to my perfect reading conditions. Twelve issue hardcovers are easy to handle and read, unlike Absolute editions or Omnibi. While I absolutely LOVE the production design on books like my

All of these factors lead to my perfect reading conditions. Twelve issue hardcovers are easy to handle and read, unlike Absolute editions or Omnibi. While I absolutely LOVE the production design on books like my